Academic Freedom vs Academic Responsibility

In my professional career I've always considered myself first and foremost, a teacher. I began teaching at fifteen-years-old, continued in K12, and as a coach, trainer, and facilitator in higher education. A teacher mindset guides my work and interaction with people. For example, I'm constantly thinking after coaching or training sessions with colleges, "Did I teach that well?" Given that I care deeply about pedagogy, I'd like to discuss why institutions should consider embracing the term "academic responsibility" over "academic freedom." The former leads to a continuous improvement mindset and equitable student outcomes. The latter is a vestige of a time that put students second and long represented by abysmal student success data.

First, so how did I start teaching at fifteen?

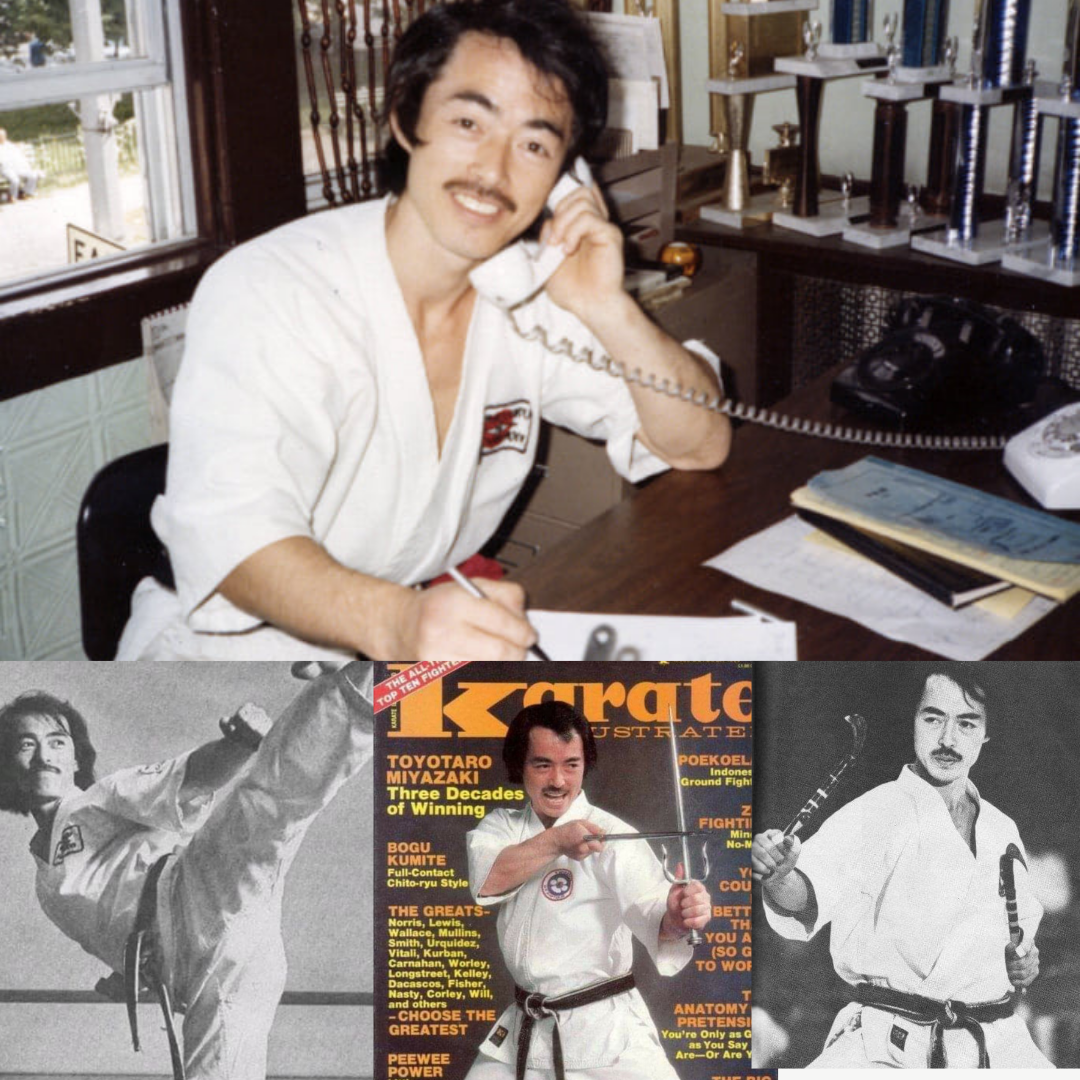

My mother, a limited English-speaking single-parent, invested her hard-earned money from multiple jobs to enroll me in karate when I was about ten-years-old. It was perhaps the best investment she ever made. It kept me off the New York City streets (mostly) and provided me with a positive role model and teacher, Sensei Toyotaro Miyazaki.

Unfortunately, when I was a teen, my mother could no longer afford lessons. The kind and generous man that he was, Sensei asked me a question in his deep Japanese accent, "Do you know how to clean?" Soon after I began cleaning the dojo every day after school and on Saturday mornings. I was a horrible janitor, but he was patient with me. A couple of years later Sensei gave me the opportunity to teach the children's classes. He didn't hand me a booklet with teaching directions. Rather, a culmination of tips as he observed my teaching amounted to a 4-step process. Sensei taught me:

1. Plan the content.

2. Visualize the sequence.

3. Implement and adapt the pace and content as you see students perform.

4. Reflect on your lesson.

I taught classes for about three years, moving over to teach some of the adult classes, and eventually assisting with tournament coaching activities. It's only as an adult that I came to fully appreciate Sensei's 4-step process, especially step 4: reflect on your lesson. Could I have done a better job teaching the class? What do I need to improve for the next class? In short, Sensei instilled in me a continuous improvement mindset.

There's another important lesson Sensei taught me. He once said, "Teach the students you have, not the ones you wish you had." You see, Sensei understood equity. He knew that people came from a variety of backgrounds and abilities. He understood that the teacher's responsibility is to ensure their learning. To do this, I may have the freedom to teach the karate curriculum with my own flavor, but NOT if it isn't getting results for students. Instead, Sensei instilled in me that my teaching responsibility was far more important than my teaching freedom. For all of us who had the privilege to teach at the dojo, we knew that a "teaching responsibility" mindset ensured that we taught the students that we have and to forget any notion about teaching the students we wish we had. I can't emphasize enough how critically important this mindset is, especially for people like me because karate came relatively easy to me.

A continuous improvement mindset along with the notion that I have a responsibility for my students' learning was the strongest foundation I needed when I began my career in education as a K12 teacher. Fast forward a bit, as a young principal, I helped to take a school to earn the US Department of Education's National Blue Ribbon Award for improved student achievement. We focused primarily on one thing: improving teaching. These experiences inform my work in higher education.

As higher education undergoes tremendous change, we hear all the time, "We must use an equity lens." How does an institution do that most effectively though? Given that students spend most of their time in the classroom, it means having the courage to transition from academic freedom language to academic responsibility language. This notion is grounded in Sensei's comment about teaching the students you have and not the ones you wish you had. [1]

I want to be clear. I'm not suggesting to do away with academic freedom. Having worked with hundreds of faculty, I know that the ones who truly care about continually improving their craft interpret academic freedom as a way to be creative and innovative to ensure student learning. I would support that notion if that's how academic freedom was universally defined. The problem is that, depending on the institution, division, department, or individual, academic freedom means different things to different people. Academic freedom is most dangerous when it's used to hide from the responsibility of shitty teaching and grading--the practices that perpetuate inequitable student outcomes that, more often than not, hurt students of color the most. It's worth noting that "weed out" and "rigor" are terms often used to justify ineffective teaching.

It’s not my intent to blanket critique faculty and their academic freedom. Rather, it's a critique of faculty who are, as I call them, "institutional conservatives." (It's worth noting that institutional conservatives include non-faculty as well.) These people fight to maintain, for a variety of self-interested reasons, the status quo. They block or sabotage efforts to implement equity-minded teaching practices and efforts to improve the institution overall via the guided pathways framework. Ironically, some of the most ardent institutional conservatives are social justice and equity warriors who care more about equitable outcomes outside of the academy than they do inside of it. They work hard to subvert efforts such as developmental education reform and guided pathways work.

Interestingly but not surprising to me, I find that it's mostly Black faculty who have had the courage to challenge the notion of academic freedom. I even heard calls from Black faculty to make all instructor course success data publicly available. They embrace transparency, continuous improvement, and refuse to hide behind the academic freedom protective veil that's used to steer the conversation away from or rationalize inequitable course success DI data.

Sensei would look at low course student success DI data and recognize that the freedom to teach any way one wants isn't getting results because the notion of teaching responsibility has fallen by the wayside or its non-existent. I would suggest that if a faculty member's student success numbers are low, that means he or she needs help. Students’ lives literally depend on it.

Here are four suggestions that could help an institution to truly implement practices "with an equity lens" from an instructional perspective:

1. Faculty must get to know who their students are and their success rates by DI population.

2. Embrace professional development offerings. It's often the usual suspects who already teach well and want to continually improve their craft who take advantage of PD. The one's who need it the most are usually absent. It's not a sign of weakness to ask for help. It's a sign of strength.

3. If insisting on using the term "academic freedom," ensure that its intent and outcome is about the freedom to continually improve one's craft to ensure equitable student outcomes. But if the culture of the institution is such whereby "academic freedom" is essentially used to hide behind ineffective teaching and antiquated grading practices, equity-minded faculty must start to infuse the term "academic responsibility" in all meetings, settings, and documents.

4. Faculty should collaborate to continually improve their craft where they focus on evaluating the teaching practice and not on evaluating the faculty member. (See Ensure Learning & Equity.)

I can hear the scuttlebutt now. "Did you read Al's latest piece? He's anti-academic freedom! He must be anti-faculty!" Nothing could be farther from the truth. I would be happy to provide faculty references, including from academic senate presidents who will vouch for me. It's because I care so deeply about faculty's critical role that I continually push our thinking, and provide resources to boot. As a student veteran at a community college, there's no way I would've transferred without key faculty who truly cared about their teaching and who mentored me. I think students deserve my community college experience, especially our disproportionately impacted student populations. I believe in the community college system and higher education in general. I made sure my kids enrolled at a community college. They would tell you how much they loved community college faculty over their four-year university faculty, but they would also tell you how some community college faculty need a significant amount of help to improve their teaching and grading practices.

Words matter. Academic freedom is a vestige of a time that put students second. It's the kind of language that's used at highly rejective institutions like Harvard, but community colleges and open access universities are better than that. While Harvard and the like pride themselves in excluding the most number of students, community colleges have the privilege to teach and serve the greatest number of Black students, former foster youth, veterans, LGBTQ students, students of color, the poor, etc. It's a privilege to teach these students, not a burden.

Academic responsibility is more deserving of a community college's mission. This language puts students first. It's also the kind thing to do.

Lead with kindness.

Oss!

(A karate term stated loudly while bowing to express warm respect and friendship.)

***

In case you're interested, click HERE for footage of me from the late 80s.

While the fighting aspect came in handy in tough situations in NYC and in the Marine Corps, my love of the martial arts stems from the spirituality and self-discipline it provides me, and its teachings about treating all people with respect and kindness.

HERE's a more recent clip. Training helps me stay healthy and grounded.

[1] It's refreshing and heart-warming to learn that faculty members, Sara Golddrick-Rab and Jesse Stommel, wrote about this very thing! https://www.chronicle.com/article/teaching-the-students-we-have-not-the-students-we-wish-we-had/

***

I'm heartbroken by Miyazaki Sensei's passing.

1944-2021