Inclusive Leadership with Dr. Bernardo Ferdman

LISTEN TO THE EPISODE:

Learn the complex paradoxes of inclusion and discover strategies to navigate and address them effectively.

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube

In this episode, I interview Dr. Bernardo Ferdman, psychologist and principal of Ferdman Consulting. We unpack one of his articles, Paradoxes of Inclusion.

(Scroll down to access the transcript.)

We discuss the following topics:

08:17: Context for inclusion.

09:37: Introduction to paradoxes of inclusion.

13:43: Three types of paradoxes of inclusion.

21:10: A paradox in higher education.

30:02: First paradox and addressing triggering terminology

41:10: The second paradox, boundaries and norms

54:34: The third paradox, safety and comfort

Select Dr. Ferdman quotes:

"Inclusion is about balancing both comfort and discomfort and making discomfort more equitable."

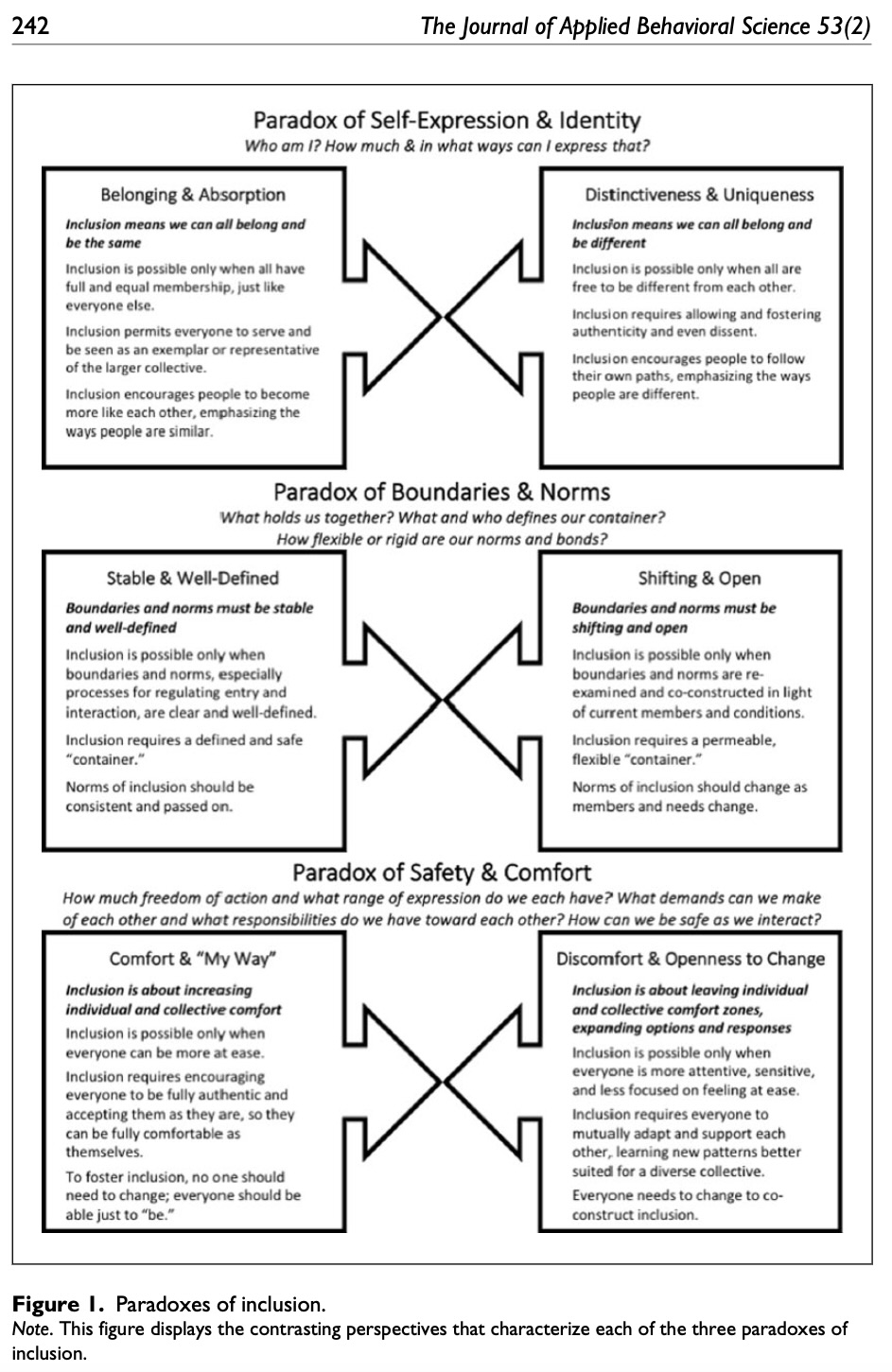

"There's three paradoxes I've identified. There's a paradox of self-expression and identity, which has to do with who am I, how much and in what ways can I express that in a group, organization or community setting? Do I need to change somehow to belong and be part of the group? Or do I need to stay the same and let it just be me without changing for that to be an inclusive experience? The second paradox is about boundaries and norms. What holds us together? What defines our container? Who defines it? How flexible or rigid are norms and our bonds to each other? And so inclusion could be thought about in terms of stable and well-defined boundaries and norms not changing or in terms of shifting and open norms that are changed to adapt to new people or changes in the people or the membership. And so that's another tension or paradox of inclusion. The third one is about safety and comfort. It's about how much freedom or action and what range of expression do we have, what demands can we make of each other? What responsibilities do we have to each other? How can we be safe as we interact with each other? And so is inclusion about more individual and collective comfort, or is it about expanding our comfort zones and our options and responses? Those seem to be an inherent tension, even though they're two sides of the same inclusion coin."

About Dr. Bernardo Ferdman

Bernardo Ferdman, Ph.D., has focused his career on supporting leaders and organizations in bringing inclusion to life. He is an internationally recognized expert and thought leader on inclusion, diversity, and inclusive leadership, with over 39 years of experience in the U.S. and around the world as an organization and leadership development consultant and executive coach. He is passionate about creating a more inclusive world where more people can be fully themselves and accomplish goals effectively, productively, and authentically, and he works with leaders and employees to develop and implement effective ways of using everyone’s talents and contributions and to build inclusive behavior and multicultural competencies. Dr. Ferdman is principal of Ferdman Consulting, and he is Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the California School of Professional Psychology, where he taught for almost 25 years. Bernardo has written extensively on inclusion and inclusive leadership; his most recent book is Inclusive Leadership: Transforming Diverse Lives, Workplaces, and Societies.

Ferdman, who immigrated to the U.S. from Argentina as a child, earned a Ph.D. in Psychology at Yale University and an A.B. degree at Princeton University. He is a Fellow of various professional organizations, including the American Psychological Association and the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, and was the recipient of the Society of Consulting Psychology’s 2019 Award for Excellence in Diversity and Inclusion Consulting.

About Dr. Al Solano

Al is Founder & Coach at the Continuous Learning Institute. A big believer in kindness, he helps institutions of higher education to plan and implement homegrown practices that get results for students by coaching them through a process based on what he calls the "Three Cs": Clarity, Coherence, Consensus. In addition, his bite-sized, practitioner-based articles on student success strategies, institutional planning & implementation, and educational leadership are implemented at institutions across the country. He has worked directly with over 50 colleges and universities and has trained well over 5,000 educators. He has coached colleges for over a decade, worked at two community colleges, and began his education career in K12. He earned a doctorate in education from UCLA, and is a proud community college student who transferred to Cornell University.

Podcast Homepage

AS [00:00:47] For today's podcast, it's a pleasure to have Dr. Bernardo Ferdman. Bernardo has focused his career supporting leaders and organizations and bringing inclusion to life. He's an internationally recognized expert and thought leader on inclusion, diversity and inclusive leadership. With over 39 years of experience in the U.S. and around the world. As an organization and leadership development consultant and executive coach. He is passionate about creating a more inclusive world where more people can be fully themselves and accomplish goals effectively, productively and authentically. And he works with leaders and employees to develop and implement effective ways of using everyone's talents and contributions and to build an inclusive behavior and multicultural competencies. He is principal at Ferdman Consulting and he is a distinguished professor emeritus at the California School of Professional Psychology, where he taught for almost 25 years. Bernardo has written extensively on inclusion and inclusive leadership, and his most recent book is Inclusive Leadership: Transforming Diverse Lives, Workplaces and Societies. Welcome to the Student Success Podcast.

Bernardo Ferdman [00:01:53] Thank you. It's great to be here with you, Al.

AS [00:01:55] Yes, thank you. So I'd like to start all podcast episodes asking guests if they wouldn't mind sharing something beyond work, something personal, a story, a hobby, a talent. Would you share something, please?

Bernardo Ferdman [00:02:09] Sure. Just so I could tell you a little bit about my background. I came to the United States from Argentina as a seven year old. So I like to joke that's where I learned the Queen's English, in Queens, New York. That's where I learned what it was to be a Latino. I've been in all kinds of minorities. I'm Jewish so in Argentina, we're in the minority. And then in New York, minority in two ways. In the Jewish community and outside also. That experience of adapting to the country and to learning English and different customs has certainly affected my whole perspective and my approach to my work and even what I'm interested in. Later, when I was 11, we moved to Puerto Rico. More adaptation, you know, a different kind of Spanish. I like to joke I'm bilingual in two kinds of Spanish. In Puerto Rico is where I learn to dance salsa and merengue at bar mitzvahs. And so people like that joke because, I mean, it's true, but it kind of made me always aware of the diversity within groups as well as between groups. And so that's really a theme in my work is really to think about both. Anyway, what I've learned and later, moving to college, I went to Princeton University, sight unseen from Puerto Rico, from the island. I couldn't wait to get off the island and broaden my experiences. But, you know, it was a different kind of adaptation to that kind of, you know, what I learned over time after a lot of years of trying to assimilate and adapt and manage dealing with the differences, which is a good learning experience, but I learned that I could do better by just being myself, you know, by really trying to ground myself and what made me me think about my experiences and my perspectives and think about how to add them to the mix of whatever group or situation I'm in. But that's always the challenge, right, is how to balance both that adaptation that we must do, but also the ability to really think about who we are and what our strengths are. And when I think about education, what's it about? It's really to try to bring out the best in people, but also support them in really doing their best in a society, in a community, in a context.

AS [00:04:19] Salsa and merengue at bar mitzvahs. That's that's such a beautiful site.

Bernardo Ferdman [00:04:25] When I got married, I didn't think it was going to be a Jewish wedding if we didn't have salsa and merengue.

AS [00:04:31] Yeah. So we have a little bit of a shared experience because I learned English. also the Queen's English, in New York City, right. Back in the 70s and 80s, which is very interesting time to live there. Unfortunately, in society there tends to be a stigma toward community colleges--that they are less than or that they're not really college or that's the easy way out for people who couldn't get into, you know, these elite universities. And nothing can be further from the truth. These are really precious institutions that open their arms to students from everywhere. It's open access no matter what your background, disability, income, right, we're going to open our arms. Now because they do that, it does make their mission, I think, extremely difficult because they always have to up their game. They have to think about how can we continually improve our craft, how can we continually improve our services because we are serving the most vulnerable student populations out there in higher ed. And so the Student Success Podcast is to help all of those who work in community colleges and broad access institutions to leave them with some nuts and bolts information, tools, resources that could be about the campus, how to improve it, or how to reflect on their leadership to, you know, continually improve. So one of things, gosh, many of the things I appreciate about your work, I wanted to highlight-- you wrote a piece in the Journal of Applied Behavioral Science on this paradox. And I was wondering if you could break that down for us, what that is. And then later on we'll talk more about application. But for now, can you kind of take us through that piece you wrote?

Bernardo Ferdman [00:06:37] Sure. I mean, the article is about what I call the paradoxes of inclusion. They're kind of 'both ands' that are an inherent part of inclusion. But I want to comment on a couple of things you said, if that's okay about community colleges, just to, you know, put it in context in terms of my connection to it. I have so much respect for what community colleges do, but I understand some of the biases that are out there. I think I could have shared them at one point. There's a challenge because we boost up these elite institutions. Right. As if somehow they're the definer of everything. And through my experience over time, I came to sort of a question that, you know, at Albany University, at Albany, they had more access than, let's say, some of the Ivy League schools. And then later I had the opportunity to work with some community colleges, particularly through the Santa Ana partnership in Santa Ana, California, when they were funded by the Lumina Foundation as part of the Latino Students Success Initiative. And that that exposure, that experience really gave me a huge amount of respect. Also, my sister teaches at the Borough of Manhattan Community College, for many years. So I can say I have an intimate knowledge of all the details. But through the years and through the various exposures and connections, I feel a very large respect. But I've also seen, you know, I have three kids, who are now older than high school. But when they were in high school, all the biases that you talked about were there. Right. But for a lot of kids, it's you know, I mean, I'm in California where community colleges are huge and really, really important and really are doing a great job. And so there's so many challenges there. So the paradoxes of inclusion, I think, might help to think about some of these. I haven't thought about it as much in terms of inclusion in education specifically, it's really thinking about inclusion in the sense of how do we create spaces where everyone across identities can feel valued, safe, able to be ourselves, able to speak up and contribute and also feel that we are an inherent part of the group without having to compromise or hide or subsume valued identities. And is that true, not just for me, but is it true for other people like me? So I may be fine. I may be doing okay personally, but if other Latinos, other Jews, other people of my identities are not feeling that, I don't feel I can say I have as much experiences of inclusion as this, other people in my group have that experience as well. So that's just a basis for where I'm coming from, for what inclusion is. Of course, equity is part of it as well. I think equity and social justice are fundamental parts of fostering inclusion and of course it has to be in the context of diversity. Inclusion without diversity is not very meaningful. Right. But it does give us a sense of what inclusion might be and then how do we spread it to people across differences. Okay. So that's the context. Is that clear enough?

AS [00:09:36] Yes. Thank you.

Bernardo Ferdman [00:09:37] When I think about the dynamics of inclusion and the experience of what's going on with it and how it's defined, I see a lot of tensions in the country. People are pulling in different directions. It's especially evident now, but I think it's been evident over time in universities. Should we allow people to say whatever they want or should we channel that? Trigger warnings, what do we do? Is that okay or not? How do we create access for people with particular disabilities? Right. If you have visual, auditory, neurodiversity, how do we address that? Does majority rule or do we make it about the one person that needs a particular accommodation or a different need? There's a lot of tensions involved in fairness. So many years ago I thought about the tensions in fairness. And so then I applied that lens to thinking about inclusion. So in that context and so what's a paradox? A paradox is when you have a situation, a person or thing that combines contradictory elements or qualities. So think about yin and yang, right? The idea is that yin and yang is an inherent part of every person. These opposing masculine and feminine pulls or styles or perspectives. Right? That idea is how paradox works. And part of the dynamics of paradoxes are that when something is paradoxical, if you pull in one direction, if a particular side of that is highlighted, the other side will sort of take on strength as well. And then that can create some polarization, right? It can pull in opposite directions more easily. Make sense?

AS [00:11:15] Yeah, and maybe could you provide an example of that?

Bernardo Ferdman [00:11:19] Let's go back to the idea of fairness, right? In the paradox of fairness with regard to whether we pay attention to people as individuals or people as members of groups, right? So we want to create equity in education or in organizations or in society. What are we looking at? Do we do we treat each person solely as an individual or do we treat them as a member of a group? The challenge is that both are true part of what people need an experience. So, this is way back in the 80s, I was working on my dissertation and interviewing Latino leaders in an organization or Hispanics as they referred to themselves at there at the time. There was the leader of the Hispanic Managers group in the organization, and he was very involved. Obviously, he was trying to promote a Hispanic voice and the presence and the role. But when he was chosen to be in a photo, a promotional photo for the company, he thought it was based on his individual achievements. And when he thought about it later and he said, wow, I was chosen because I'm Hispanic. He was really disappointed. So there's kind of an irony there because on the one hand, he's fighting for Hispanics. On the other hand, he didn't like that that identity was what he felt was the primary basis for being chosen to be in the photo. So it's almost like he split off the two things. So part of the challenge was how do you hold both of those together? I can understand the disappointment if that's the only reason he was picked, right. Because he has so much more about him that is important, his achievements, his approach to work, all these things. But he's the same person who told me that I don't feel the same at work than outside. I can talk to people about the things that mattered to me. So his experience of being Hispanic was really important to him, and it mattered in his experience. So a paradoxical frame helps us see this inherent tension in these things and helps us think about, well, how are you going to manage it? We can't manage it by choosing one or the other side. Both of those were important to him even though they felt like they were in tension. The individual frame or perspective, and the group perspective, that he wanted to be treated as an individual, which he deserved, and he wanted his group identity to be noticed, addressed and honored.

AS [00:13:38] Yeah. That is a very interesting dynamic. Please continue.

Bernardo Ferdman [00:13:43] Yeah, sure. So let me explain the paradoxes I identified. There's three of them that I discuss in that article you mentioned. I'll name them in quickly and then we can go through each one. So there's a paradox of self-expression and identity, which has to do with who am I, how much and in what ways can I express that in a group, organization or community setting? Do I need to change somehow to be to belong and be part of the group? Or do I need to stay the same and let it just be me without changing for that to be an inclusive experience? The second paradox is about boundaries and norms. What holds us together? What defines our container? Who defines it? How flexible or rigid are our norms and our bonds to each other? And so inclusion could be thought about in terms of stable and well defined boundaries and norms not changing or in terms of shifting and open norms that are changed to adapt to new people or changes in the people or the membership. And so that's another tension or paradox of inclusion. The third one is about safety and comfort. It's about how much freedom or action and what range of expression do we have, what demands can we make of each other? What responsibilities do we have to each other? How can we be safe as we interact with each other? And so is inclusion about more individual and collective comfort, or is it about expanding our comfort zones and our options and responses? And so those seem to be an inherent tension, even though they're two sides of the same inclusion coin. Shall we delve into each one in more detail?

AS [00:15:25] Yeah. Let's dive in a little bit and then we'll talk more. I'm already, my wheels are turning, within the context of what I see at these institutions and the leadership challenges that they have, the dynamics, policies. These institutions are such dynamic places and at the same time they're also inherently, here's a paradox for you, they're very dynamic, fluid places, but inherently very institutionally conservative.

Bernardo Ferdman [00:15:55] So how does that play out?

AS [00:15:57] A lot of my work is helping campuses to continually improve and to be very productive in their teamwork, having solid outcomes that they're looking at and moving forward with--I use a lot of project management tools--we want to move forward. We want to change. We want to continually improve the student experience and we want to be more intentional about the equity piece. At the same time, the system is set up almost to fail. That's what I call my three month rule, Bernardo, which states that the typical campus only has really three months in a year to get major party work done, especially because we need faculty. So summer, forget about it. Everybody's gone. Oh, September, start of the semester is too busy. October. Maybe October is okay, but that tends to be a month with a lot of conferences. November, December, holidays. Forget about it. And you know, meetings get cancelled all the time and people are out or they're too busy. January we're gone again. February. That tends to be all right. Some depending on the campus, but it's kind of started the new semester, so. So busy.

Bernardo Ferdman [00:17:12] Yeah. So there's a certain rhythm. There's a certain routine that people follow and depend on. And there's certain dynamics and forces that make it hard to change. And some sometimes for good reason. Right. Because we know that faculty can often, you know, there's a lot of contingent faculty and staff. It's a real thankless job in many cases, right? Without enough power at the same time of faculty have a lot to say. They really care about education and what's happening. I'm not the world's expert on this, but, you know, there's a certain untenable aspect of the way the system is set up. There's the challenges of getting funding. There's the demands from external forces, right, from particularly around these issues around, are we really going to include everyone truly? There's all the backlash against college degrees and all of that. In a good way, we really want opportunity for everyone. So community colleges on the one hand, from what I see here, from my vantage point here, on the one hand, they want to offer four year degrees here in California, some of them. And on the other hand, they want to do much more vocational studies, things that are short term that get people right into the workforce. They have to partner with work places, and businesses and so on. On the other hand, they're supposedly designed to create social change. So how do you create social change if you're sitting with the organizations that are keeping things the same, keeping the hierarchies, keeping certain people in their place, you know, giving them, maybe they're decent jobs, but they're certainly not going to get rich on labor-type jobs of the people who come out of these programs. Hopefully they could have a nice lifestyle. But this supposed American dream, the whole Horatio Alger story, it doesn't quite work that way. Right. Social classes are stronger in the U.S. based on data I've heard about that in many other countries. The other interesting thing about education is that we say is the key to opportunity. But another side of education says that to the extent that it reproduces this social class structure, it's doing its job.

AS [00:19:25] Yeah, there's that argument. To go back for a moment about that paradox, so not only is it very difficult to get things done, but then it only takes a few, a few who don't want change, to ensure that it doesn't happen. They can sit in the right committees, slow things down. So it could be very difficult. And then the whole committee structure is inherently dysfunctional. Back to your paradoxes then. If you can dig a little deeper into each cause, I think where I want to go with this, is because you work with organizations and I want you to kind of put yourself in the mindset of like, okay, let's say you're working with a group of community college, our broad access institution leaders. And by leaders, I mean, and this is the thing, I think this is the beauty of these institutions that you don't always necessarily need a title to have influence. So whether it's a cross-functional team that has a particular outcome in mind for students. Let's say it's to close gaps. It's a federally designated Hispanic Serving Institution. And we see a 20 or 30 point gap between certain group of students and Latinos. And we got to do something about that completion gap, for example. Right. So, but there are some cultural dynamics, and the paradoxes that you started to talk about. How do they begin to use your framework to kind of navigate these very difficult changes that they're trying to implement?

Bernardo Ferdman [00:21:10] Well, thanks for the examples. Maybe you could help me. Maybe together we can think about some of the applications implications, but those are some good examples. You know, for example, thinking about the inclusion of Latinos in community college spaces and serving them better, that's something I did have experiences worked on some of those issues. I also did some consulting with the National College Attainment Network on their own DEI initiatives. Anyway, the first paradox of self-expression identity. You can look at inclusion in two different ways. On the one hand, inclusion means that we can all belong and be the same right, have the same degree of membership and value, right? A If you're a college student, whatever your identity is. So we all share that identity, for example. So that a kind of inclusion. We want the same rights. We all want to be able to be a representative of the organization. So that's one way in which inclusion is about being, I don't mean the same identical, but I mean being similar in that sense. But on the other hand, inclusion is grounded in distinctiveness and uniqueness, not just in belonging and absorption. And inclusion means we can all belong and be different. And that's another way to think about inclusion. Then those two things kind of oppose each other, right? How does that play out? Right. There's manifestations of the paradox and people emphasize one or the other side. So on the one hand, some people might think something like or say to each other, if I can just learn the rules for success, I'll be fully accepted. So then you have in the examples you gave, you might have, the EOP program or programs that help people adapt to college and learn the rules or, you know, the English remediation classes or math remediation classes. And some of those things make sense. You need to know how to do writing, how to do math to succeed in certain courses. So that's the part around really helping people adapt. But other people might say the opposite. Like, if I want to be fully authentic to who I am, so I'm not going to ever do things their way. And then you have extremes of that that say that, in my view, that trying to write gramatically is white supremacy. To me, that's an extreme position. I would argue that you can use imposition of grammar rules as a form of white supremacy. But writing grammatically by itself is not inherently supremacist, in my view. Okay. But so it's a both then write again. So I think when you get to the extremes, you see how this paradox manifests, right? Because one side triggers the other side, and used to polarize against. Not helpful. So, for example, people talk about, why are they asking for special rules or special treatments? We should treat everybody the way we want to be treated. Right. We know how it works. Let's just do it that way. Why? Why are we going to special programs for these groups? That's not fair. But that's not acknowledging the history and the reasons for the disparities. And then other people might say, if you become like us, you're going to lose your distinctive or special edge. We don't want women who act like men or Latinos who are just like Anglos, right? And that could come from anywhere. We should maintain the difference. So a student or a person or an employee who wants to be whoever they are, maybe a person from a Latino background who doesn't speak Spanish, are we going to look down on them? Or assume that they're not Latino enough? That's not fair or appropriate either. Right. And that's not inclusion. So how do we honor the range of ways in which people manifest and think about their own identities and cultures? And some of us say don't be an ofendido , don't be a sellout. Be true to who you are or to your people. So is going to college a sellout? No, I don't think so. But so that's the manifestation, right? And then, why do we need, on the one hand, why should we treat different groups differently? On the other hand, without unique programs or opportunities for different groups, nothing's going to change. So anyway, those are the manifestations. So then the challenge is how do you manage that? Do you want to get into how you address the particular paradoxes?

AS [00:25:25] Yes, that would be great. Yeah, I'll chime in a little bit because I have a couple examples, But please, please go ahead.

Bernardo Ferdman [00:25:32] Sure. So, yeah, because there's one thing to think about it, the other thing is what do we do about it? Right? But I think the first step is to be aware of this tension. When we see ourselves or our groups highlighting one particular position and moving in that direction. It's important to think about what would the opposite side be and is that reasonable also? And under what conditions is that true? So the first step is to avoid polarizing between the two sides. So, for example, understanding that identity with a collective could allow for distinctiveness and affirming uniqueness can strengthen a sense of authentic belonging. In other words, if you affirm people's Latino identity in the context of college, they would be stronger, more strongly connected to the larger college community. And there's evidence and research that suggests that's the case. When we allow for and foster subgroup identity, it actually enhances the connection to the whole. You can think about it in terms of people's connection to their particular major or department for faculty or for students or staff. I belong to this department. It doesn't mean that I don't belong to the larger college. Of course I do. In fact, my connection to the college is stronger because I have a strong identity in that unit. Well, I think it's the same for other kinds of identities, and there's evidence to support that. And so that's one way to think about is to avoid polarization. And recognizing that, quote unquote, special interests and affinity groups serve the whole by strengthening the parts. So the other part is to understand that we're all joined together in our difference in uniqueness. It's not that everyone has is different and unique, and that's what makes us similar and connected. And so really owning that difference is part of our connection to me and equalizing it, right? Not saying that, you know, when people use the word diverse to, you know, diverse person, I, I really have a visceral reaction because there's no such thing as a diverse person. Diversity is a quality of the group and we can all contribute to it. And so diverse person is a euphemism for people who have been marginalized, who are different than the dominant group. So we really have to think about our assumptions when we use certain terms and when we think about collective identity, like the history of a school or a department or a particular organization, we want multifaceted accounts of that collective identity that apply to everyone, but also recognizing and addressing specific histories, needs, aspirations. How do we not make it all blend that there's no identity at all, but how do we make sure that it resonates and connects to all the different threads that make the tapestry of that particular group or institution? And finally, I think we have to understand to accept, to embrace. intergroup processes and perspectives. We are not just individuals interacting. We have particular group identities and our interactions are part of the larger relationships between groups. And we have to understand that even while we emphasize individuality. So earlier we talked about my own experience as an immigrant, as a Latino, as a Jew. Those things combined in a particular way. I'm also a man. I'm married, I'm cisgender, a heterosexual. I'm now considered a senior citizen. You know, it's a whole identity as well as a life transition. But I'm unique in the way those things combine, right? But it's not just at the individual level in the sense that each of those threads connects to larger intergroup processes and dynamics, and I have to be aware of that when I interact with someone, they're seeing a man with a particular size, with a particular color, with a particular way of speaking. And so they're not just interacting with Bernardo, you know, they're interacting with all of those identities and I'm interacting with theirs. So if I meet a student at a school, and they see a professor, you know, if I'm a professor and, you know, I just deal with me as an individual. Well, we still have our roles and our ways of being, so we really have to hold both of those. And that's part of the way of dealing with this paradox.

AS [00:29:54] There is so much there.

Bernardo Ferdman [00:29:58] Yeah, we already did one of the paradoxes.

AS [00:30:01] There is so much there. So I'm a very practical person. I consider myself a coach with colleges. I help them through productive struggle, but I'm so practical in getting results, I want to see improved outcomes for students, especially for those who are most vulnerable. And when there's equity gaps, I have a lot of success in actually closing. And because I'm practical and because what I like to say in my work is that there are these equity, because in higher ed, it's really become such a, especially after George Floyd, the word equity and doing equitable work has really been highlighted and every campus or I would say you probably would agree in other industries there are what I call equity yellow lighters, meaning that, especially when it comes to racial equity, that they're like, you know, I don't know, I'm kind of against the fence. Should we help all students? You know, do we really need to, you know, do it this way, really help these marginalized? Well, we should be helping all. And then you have your your green letters, right? These people, they embrace it. They try to do equity intentionality. And then you have your red. Right. Well, and a lot of my work is turning those yellow letters to green. And it's not through lecture. It's not through insulting them. But actually through the work, I help them think about why it's important to be more intentional about the equity piece. Sometimes I move the red to two to green. Not a lot. But what's happened in the last few years is that I've seen some yellow lighters stay at yellow or actually moved to red because terms like white supremacy I think have become and colonialism become kind of abused and watered down. I'll give you an example. I've seen this a few times and I'm like, wow. So complaining that to come to a meeting on time and to have a structured agenda is colonialism. So at what point is someone using colonialism or white supremacy for something that they personally don't like? Right. And so what happens over time is it really and don't get me started on some of the consultants they bring over from and how they insult without even providing any kind of tools and resources to, you know, improve themselves. They just throw these words. And people are supposed to turn from yellow to green by being called names and not given tools to change. So I wanted to highlight that a little bit because you had mentioned that as well, and that could be a wrench in the work, right, when we have this paradox when people are abusing a particular terminology. Have you seen that outside of education?

Bernardo Ferdman [00:33:14] I think, look, I think there's people who are great at doing certain things and some who are more challenged in every field, right. I mean, I think there's going to be a range and how that gets perceived, the experience is going to be different for different people. I think there's a in my view, there's a real history of racism and racial oppression in the United States and to some degree around the world. Noticing, addressing it. We have to find ways to do that. Right. And, you know, if you look at the wealth gap in the United States, you can directly connect it to enslavement of a of people and the aftermath of that, you know, the continued exclusion of people of African descent and others, people of color in the US. So there's a lot of data about that, right? That doesn't always apply in every individual case, right? But there's a certain group reality. Now, if somebody is using certain terms on me in a way that I don't find helpful, like, you know, because I wanted to have an agenda or have the meeting at the time that we scheduled and blames, you know, tells me I'm being colonialist, that's challenging. But understanding where that's coming from and the motivation and the feelings of all, to me, that's part of creating a space for inclusion and dialog, right? We have to be able to hear each other. Otherwise we just move into extremism. If I just shut that person down, I'm just doing to them some of the very same, whatever you want to call those dynamics, right? I don't believe in shaming and blaming in creating inclusion and trying to foster conversations and fostering equity. I think we have to find some some mutual benefit also. Right. Equity is not about taking from, you know, just simply redistributing. Right. It's something that's going to help everyone. The lack of equity hurts even the beneficiaries. In fact, psychologically, people are motivated to create equity, right? We do it sometimes in some cognitive ways, right? When we rationalize why we deserved more than others. But but most people are not saying that everybody should be paid exactly the same. They think even in the workplace. In the United States, most people are probably okay with different salaries for different kinds of jobs. So the question is, how does that work? How do you allow for inequality? That's fair. Right. Equality is every bit exactly the same. But if you have a college degree or if you have certain skills, you figure, well, you should let people do certain jobs compared to people that don't have the skill part. So we have to break it down and have those conversations. And if we just get into this back and forth about this is right, this is wrong, and we don't try to have a conversation, I don't think it's going to work. So I get your discomfort. But if you just completely exclude someone because I want to know what's at the root of it, how is that issue of time being used to continue to oppress people? Right. Because we know that there's certain associations people have about cultures and people that are related to things like that. So I think we have to soften our approach. And also and I think on every side. Right. In other words, I agree with you that using certain terms be a bludgeon. It can really be a way to shut down conversation. But understanding where it comes from and understanding that there really was a certain dominance of some cultures over others historically and currently, that's something to think about and unpack, right? And then we can talk about where does it manifest, how does it play out in our lives? I may not have the intentions of imposing certain things on people, but I do you know, I felt, you know, I was a psychology professor. Right. But I felt like an English professor sometimes, and I can tell you what a burden was lifted from me when I finally stopped trying to correct pronoun usage in papers and student papers, and they would use they as a plural pronoun, as a singular pronoun. And I constantly would be fixing it. And I did. Not only did I give up, I realized I was wrong. You know, also I was always trying to correct everyone's spelling. And I would use it as an indicator of other things when somebody was misspelling or making mistakes. And then I read Gabriel Garcia Marquez, his autobiography, and he said, you know, the Nobel Prize winner from Colombia, and I loved his books, you know, always. He said that he couldn't have survived without a copy editor because he couldn't spell at all. He was terrible speller, I guess. I don't know if he was dyslexic or what, but he couldn't spell. And he's an amazing journalist, amazing writer, brilliant, incredible mind writing. I always admired it and loved it. So that also helped me realize, wait, why have I been so, I've been biased. I have to really think differently. You know, and it's hard for me, I have to admit. But it helped me realize my own participation in interpreting certain things that people did in a broader way than was justified. But that connects to group things like neurodiversity or dyslexia or even just the opportunities people have. Right. So, if somebody writes "gonna", instead of "going to" does their idea get invalidated? And so that's something I had to work on. If I were to teach in a community college, I'm sure I'd have to deal with my Princeton and other, you know, well, kind of inspired kinds of wiring.

AS [00:38:51] I wish people would have those conversations that you're talking about because, but here's the thing, Bernardo, the people who receive that perpetuating colonialism, they don't ask because they know better. They know that if they ask, it's just going to go down a rabbit hole of potentially even more lecture and shaming. Right. So what what I've seen because I work with so many colleges. Right. And so many teams is that when they are told that--and the agenda is about equity, by the way--it's not about suppression. The agenda is actually about how are we going to improve and we want to start on time, right? So the content of it isn't the issue is just the fact that we're coming on time and that there is an agenda, right? And so what happens is that these people who who's saying that, you know, you're just a colonialist, then what happens is that they they shut down.

Bernardo Ferdman [00:39:54] One of the questions is, do we frame these as positive conversations about how can we do better and what what does better look like depending on where we stand and what are our experiences. And so we could critique that particular person, but we could also think about who is deciding what the approach is going to be and are we willing to have a more difficult in a sense, but ultimately better approach that's more strategic, that's not just about checking the box or training or saying we had this thing, you know, do we think about, do we create an inclusive process for fostering inclusion and equity? Right. We need that. We have to create it here and now, that we have to be experiencing as part of the process. In other words, it's doing a one, you know, lecture that says this is the truth and that's it, and there's no dialog, to me that's not inclusion. We need a framework, a model, a perspective on what inclusion is. Now, do we have to consider historical intergroup relations and patterns? Probably. But at what point in the process do we use that to make people feel bad or like they have nothing to say? Personally, that's not what I do and what I think works. But maybe that's getting us into the next paradox. If you want boundaries and norms, right? It's about on the one hand, inclusion means that we need stable and well defined norms, right? It's only possible to have inclusion when we have boundaries, norms that are clear. Processes for regulating entry and interaction. For example, how do we talk to each other? We don't want all hell to break loose. So we want to have ways that everybody's voice to be there. We want to have some norms and values. So in universities or organizations where you have values of inclusion, you also have ways to regulate speech, not to regulate in a bad way, but to say, you know, we want to have free speech. But we also don't want to hurt each other. If the speech results in people feeling like they're less than or don't belong or or stereotyped or harassed, we want to do something about that. Right. And I know there's debates about where that light is. But the point is we need some kind of regulation of some sort, right? If teachers bully students, obviously that's not okay. So we need some norms. We We need to know like, okay, you shouldn't misgender your students, for example, if you want to be trans inclusive in a school or organization. So those are just some examples of why it's necessary. Also for inclusion, we need to define a safe container. What is it that you're including people into? If it's like totally fuzzy and you don't know what the space organization or unit is, what is inclusion even mean? And also we should have norms of inclusion that are consistent and passed on that help us understand what is like when you think about civil society, right? I mean, I think about the US Constitution. I think about laws and regulations. Otherwise there's anarchy and I'm not sure that's a way to have inclusion under anarchy. So that's one side. But the other side says, okay, for inclusion, we need to have boundaries and norms that are shifting and open. We can only have inclusion where we reexamine and construct our norms and boundaries in light of who the current members are and what the current conditions are and who what prospective members are. We also need a permeable, flexible container for inclusion. We need to be able to add other people to create more difference and notice the difference. And we need to change the norms of inclusion as members and needs change. So this example we were using, which I don't know how far I can go, but this idea of timeliness, for example, what does that mean? What flexibility do we have for different people? I mean, I think about, you know, the rules around handing a paper in on time. Well, what kind of flexibility is there? If you have students that are going through food insecurity or sleeping in their car or have other health challenges. Right. Or taking care of their parents who don't speak English or something like that and helping them navigate the social, you know, whatever. Can I be flexible as a professor or as an institution? Probably I should be if I want to be more equitable and more inclusive. On the other hand, if you just say whatever is that really the kind of institution or situation, probably no. So how do you negotiate that together? What is the voice from the people who are affected? So that's, I think, moving in the direction of thinking about how you manage the paradox. It's a "both and." So you have to both recognize it, own it. We have internal ambivalence about boundaries or norms even individually. On the one hand, we need that structure and that predictability. On the other hand, many of us might chafe at certain restrictions. So back to your example about complaining about timeliness and agendas. Then the question there's probably an underlying question like who defines the agenda, right? Maybe that's a way to to protest against the idea that we can say, you know, when people say in a conversation, well, for the sake of time, let's move on, what are we suppress it? Right. So I'm trying to see the commitment, the need that's underneath this thing that feels wrong.

AS [00:45:15] Yeah. And really quickly, just to let you know, because I work with about 60% of my almost 70% of my work is with faculty. We have moved from, because there's some really bad, antiquated practices where faculty were literally closing their doors to the classroom when they started. Right. And this is a community of students who work three jobs, single moms, single parents. Right. And so that's extreme. And so we worked a lot on syllabi and policies and how we can be more flexible. But there's different levels of flexibility. And what we found in doing this work the last few years is that when we go too far and the flexibility students are telling us, we need, I need a little bit of accountability. I need a little bit of structure. So there's kind of this middle ground and it varies by faculty, but at the end of the day, they're more flexible and they're handling more on a case by case basis. Right. There's kind of some middle ground. So I just wanted to mention that because it's been a learning experience for faculty to move away from such a strict way to too much flexibility, which students are saying, wait a second. Right. So they're learning that middle ground.

Bernardo Ferdman [00:46:38] Yeah. And it's challenging. It's hard sometimes to have this "both and" of these two opposites. Sometimes it's a way to deal with anxiety and with insecurity. When you say this is the rule. Take it or leave it. Too bad. But then it's not going to be helpful for some of these challenges of inclusion and equity. I make no exceptions for anything, well, are you sure that you would never want an exception for something? What if one of your family members dies and you can't go teach that day? Do you really want to do that to yourself? Part of the challenge is finding where is that space for some learning and dialog and flexibility. But also, as you pointed out, what are the needs for structure and boundaries? And I think part of that is the co-construct. So co-construct the norms and processes for inclusion with clear parameters and hold each other accountable instead of just assuming that my movie of the rules is your movie, let's talk about it and make sure that we agree and then remind ourselves. You know, when I taught a course on diversity for many, many years, we used to co-create the norms for the semester. One of them was always confidentiality. And it's interesting. Or others like that. It's interesting because what the norms did, it's not that people would never break them, but it created a collective space, a collective opportunity to talk about what people might have perceived as possible violations. It wasn't just like, I just want to bring this up as an individual. It's a collective need and imperative to have that conversation and we would make space for that in each session is to remind ourselves of what the norms were and allow for anyone to say, what else do I need today? So it's really a human process of checking in around these the process. Other ways to manage this paradox is to engage across differences in the spirit of learning and possibility that we should expect to engage across different approaches for engaging across differences. People have different views about these things, about the need for flexibility versus structure and goals. We have to understand that inclusion implies both loosening boundaries and at the same time enhancing them for new and different people to feel included. The overall category has to be clear, but at the same time has to be redefined. Like what's an American? When my kids were all born in the USA, say, they refer to Americans as you know, they refer to Anglos as Americans. I say, no, you're American. Because American is everyone, right? American can be all these different. So what's a college student? I think we need to broaden some of these ideas. And also, inclusion doesn't mean the absence of limit so that anything goes or that you can question every possible thing. So we still have to understand what are those boundaries? What do we mean by inclusion in this particular time at this particular group? We also have to create and use rules for dissent and rule breaking. What are the rules for rule breaking? Which is kind of paradoxical in itself. And we have to have a collective definition of the boundary of the unit of the collective based on shared values, but also hold space for divergent values. So in a university or college, a learning space, I think that's particularly important, right? What is the collective value? But understand that some people may not share it in the same way or mean the same thing. But the last thing I would say about this is that we have to work with those who are present. There's always this fear of the slippery slope, right? Like, you know, on the one hand, on this paradox, one side of the paradox is people might say it's a slippery slope. If we change our rules or open that conversation, we might as well just give it all up. But, we have to work with who's there, but we also have to make space for newcomers and their possible dissent or discomfort or a need to change our assumptions. So, we're recording an audio podcast. You know, how do we make it adaptable to someone who has a hearing disability? Maybe there's technology now that can help with that, obviously. That's just an example of how we have to think about accessibility in a way that makes sense, that's reasonable, that creates the broadest possible access. But that doesn't solve every possible puzzle right away because then we'll get stuck and we won't do anything.

AS [00:50:56] By the way, I always have transcripts available, so. Yeah.

Bernardo Ferdman [00:51:03] Well, there you go. Thank you. Thank you. And I love that because you addressed it immediately. We didn't just leave it hanging. Right. We think about that. The other side of that slippery slope argument is we need to get everybody's input and consent before we act or we might offend somebody. That's part of the paradox. This is focus on shifting and open boundaries. We're never ready just to settle on anything because it's never going to be right or we didn't create the system. It's not ours or appropriate for us. Why should we follow their principles and practices for engagement? Well, okay, so what would you like to do? And that somebody else might say, what are they going to ask for next? Nothing's familiar anymore. I have to walk on eggshells all the time. You know, it's like just, you know, let's just follow the rules.

AS [00:51:50] These paradoxes. I think what you've done, in my view, is to give us some language to, and a framework, I'm going to have it on the show notes. I'm going to have a picture of that diagram. It's another way to really think about the challenges. We kind of know this in our head a little bit. We experience it all the time, especially I see campus leaders dealing with these paradoxes. But you've put them in words. You gave it language. And I'm wondering, as we wrap up here, I'm just thinking out loud here. So would something practical be, obviously would be great if they can have you come over and and you can consult with them to break this down and help them, you know, apply this. But like me, I think you're kind of a one person show. And so you can only get so many people that you can help. But for those that you can't reach, something at least that the very least that they can do, can they take your paradox sheet, and use it either as a self-reflectiving kind of worksheet where they answer your questions for each of the paradoxes and/or do you feel like that's something that a team could use, like an executive team at a college or even I got to tell you, some of the most dysfunctional, because I love faculty, I work with them all the time, but they're even the ones who tell me, shit, Al, our academic set of meetings are a hot mess. And I think they're dealing with a lot of these paradoxes that you're talking about. So is it good to kind of use that in a team setting too what's your guidance on using your framework?

Bernardo Ferdman [00:53:42] Well, I think you pointed to some of the ways. I think, first of all, I yes, I work on my own, but I also partner with other people, just to be clear about it.

AS [00:53:50] Thank you for clarifying that.

Bernardo Ferdman [00:53:52] Yeah. But I, I think that the first step is to realize that sometimes when we see, when we're experiencing a strong reaction, a strong perspective, a really strong stance, the leadership challenge or the challenge for all of us is to think about, okay, what's the other side? And if I let go a little bit of my certainty, is there some reason there? Is there some way in which that makes sense. And to what degree does my thinking about this actually trigger the other side to be even stronger? And that's a clue that maybe there's a kind of paradoxical relationship between these things. We didn't get into the last point about safety and comfort and just I'll use that as an example. Right. Inclusion, on the one hand, is about making everyone comfortable. On the other hand, as my father used to say, stretching my arms to be, comfortable-- my zone of ease of stretching out ends at the other person's nose. So we have to adapt to each other. We have to leave our collective zones. Inclusion is about balancing both comfort and discomfort and making discomfort more equitable. Right. Some people are more used to adapting and be uncomfortable, and others just do whatever they want. Well, you have to balance that. So I think starting to see the systemic relationship of the different pieces, that's the first step, is to not just get entrenched in our position in a way that actually makes the other side stronger. If I try to just eliminate the other side, the likelihood is that's going to pop up even more strongly, right? It's not going to make it go away. And so we have to look inside and look at our own ambivalence about some of these issues. How easily do we swing back and forth? That's just a way. But we can do that as a team also. We can bring in before we settle on something, we can ask people like, is there any other view here and really honor that and work together to make better decisions and have a better perspective. So that's the norms. Again, the processes that we follow that will allow us to hold the these seemingly opposing things as part of the same phenomena. That's just some examples. I know we don't have a lot of time, but maybe you can think of additional, but some of that might be systematically brought it like through processes that are followed. Let's make sure to ask, for someone to to kick the tires on this idea. And what are the unintended consequences of this position or for all falling into line so quickly? You can ask the question, who's missing in this conversation? Or to rotate, not to blame the person who brings up the opposing side, but just to see how that's really playing, doing something for the group, right? Instead of saying there's something wrong with that person. So really reframing is important. And that's where the leader, the the person in authority, the chair or whatever can really make a difference in how they address these kinds of issues. Are they holding space for difference in both the process and the content? I think ultimately that's for me, the bottom line, and then of course, the specific attention to these to these paradoxes. But there may be other ones that people are experiencing. I don't think these are the only possible paradoxes.

AS [00:57:10] And by all means, Bernardo, if you want to continue with the the last paradox, please, by all means. It's not like we have a set time.

Bernardo Ferdman [00:57:20] Okay. I started to explain it, I think just again, just to think about it, on the one hand, you can certainly believe that inclusion as possible only where more everyone can be more ease. We encourage everyone to be fully authentic and accept them as they are so they can be more fully comfortable with themselves. People say like, be your whole self, right? And this and that as the comfort side of the paradox. My way. I'm going to follow my way. So to foster inclusion, no one should have to change. So everybody should just be able to just be right. I should be comfortable being me. But the other side is that we have to adapt to each other. We have to leave our comfort zones. We have to expand our options. So inclusion is only possible and everybody is going to be more attentive, more sensitive, less focus on personal comfort and feeling at ease, and more on how do we do this together. When we mutually adapt to support each other and we learn new patterns that are better for a diverse collective right, not assuming that everybody wants to learn, talk, interact the same way as me and that everyone needs to change if we're going to construct inclusion. So how do we hold both of these? If you think about the extremes, it's when people say, I feel like I have to walk on eggshells, like whatever I say, they get offended. That doesn't feel inclusive. I should say whatever I want. Isn't that free speech? But the other side is how do we create inclusion if we just leave things as we are, as they are, we need to change it up, keep things fresh or on the other side. Why can't we do things the way we're used to? We can't even have fun anymore. Like all these new rules, like how do we move? But the other side is like, Hey, we can't really do it the same way and expect that we're going to have equity and inclusion because those things that you used to do keep people uncomfortable. You know, the locker room talk, the exclusion of people with disabilities or people are saying things like, why should we process and check in on everything? Why can't just get to work? It's just about let's just be professional and be respectful. But on the other hand, the word professional is such a culturally loaded term. What does respect actually look like? How does it manifest? And then others might say on the other side, we can't get work done and collaborate until we spend time and effort figuring out how we're going to do it. How else are we going to deal with all these differences? I think that's a good idea. But when it gets to the extreme, all we're doing is spending time talking about how we're going to work and then when are we going to get the work done? We have to find that balance that doesn't resolve it, right? It's holding these two things in tension and we're constantly kind of going back and forth. And so we have to understand and accept that comfort has limits and self-expression and self-determination have to happen in a collective context where we mutually understand and collaborate with each other. We have to engage in ongoing dialog and learning. Be willing to learn new ways to do things and to engage with others. I have to honor what you want or how you want to be treated rather than how I want to treat. But you also need to understand that I have certain history and pattern and experiences that give me time to learn. Instead of hitting you over the head. Growth and learning are essential part of being human. So we're always growing and developing. So this idea of being your whole self like, what does that mean? Why not be your best self? Keep growing and keep developing. And education is about that, right? We don't assume that people are fixed forever. We're assuming that people can develop. So if we're the educators, how are we developing? How are we developing our organization? And becoming more myself requires growing and learning, especially from people who are different or we don't understand. So this idea of engaging across difference is not just important to hold diversity and for equity, it's important for everyone's learning. It benefits everybody. And so ultimately, we need to learn to be uncomfortable and to understand that those whom we don't understand are important in our own path and our collective work. Just being at ease all the time is not going to help us do our best. I mean, think about going to the gym, right? If I never strain my muscles a little bit, I'm not going to get stronger muscles. But if I strain them too much, obviously they could break. So where is that balance? It's different for each of us, different for each group. But the willingness to explore it, to me is one way to apply this paradox frame.

AS [01:01:41] For me, the way I understand your meaningful work as a practitioner is I'm seeing this as a first step is to be hyper aware of these paradoxes. Just that self-awareness and that awareness that these are happening. But then don't just leave them in your head and say, well, that's just how it is. But the second thing is I think I can probably summarize it as empathy, where we want to start to understand the other positions. We may not necessarily agree with them, but at least now we're getting it out the open. There's conversation, at least. No one's being shut down. And there's a level of learning, understanding about these paradoxes. And so in a way, this is kind of like a cultural or culture barometer, if you will. But here at the end of the day, they're going to have to make decisions based on these paradoxes. And that's the difficult part. Right. And it's a process of learning. Now that I see this paradox, how do I actually address it? How do I bring people together to move forward in a very kind way, productive way. I don't mean to reduce all your beautiful work. And to me, that's how I interpret it. That's how I internalize it.

Bernardo Ferdman [01:03:17] Well, that makes to me, I think. Yes. I think just to reflect back, I think it's you know, I don't know about being hyper, but certainly aware. I think certainly understanding that polar tensions, polarization can sometimes be framed as two sides of the same coin. And to the degree that we develop that perspective on these dynamics, that can help us bring those elements back together. Part of making a unit whole is holding space and holding these contradictions as part of the the group or the organization understanding that if you just try to squelch one side or kick it, expel it, it's not going to resolve the issue at all because it's inherent in whatever whatever the issue that what we're trying to do. And so I think that's the broader paradoxical lens, and then I've applied that to specifically inclusion, in thinking about these three dynamics that are particular to inclusion. But I think if you apply this more broadly, I think it can be really helpful when you think about what's the "both and" in the situation, the "both and" with two things that seem opposed to each other and feel contradictory and yet are two parts of the same phenomenon or situation or thing.

AS [01:04:37] And my last question, Bernardo, if people want to connect with you and need your help, I can put your website there. But is there anything else they need to know about how to contact you? And is there a process to this?

Bernardo Ferdman [01:04:51] I'm easily found on LinkedIn. I'm also, like you mentioned my website Ferdman consulting.com and I have a contact form there. So it's pretty easy to reach me there. And you know, otherwise people can probably find my email somewhere, but I think those two first ones are easy. I'd love to hear from your audience and see how they're thinking about these issues and how they're applying it in community colleges in particular are so important. So I do hope that there's some nuggets that will be helpful in making them even stronger and better.

AS [01:05:26] Thank you so much for your meaningful work, Bernardo, It's such a pleasure to talk with you, to learn from you. Thank you so much for participating in the Student Success podcast.

Bernardo Ferdman [01:05:37] Thank you. Thanks for this opportunity and thanks for your work. Al.